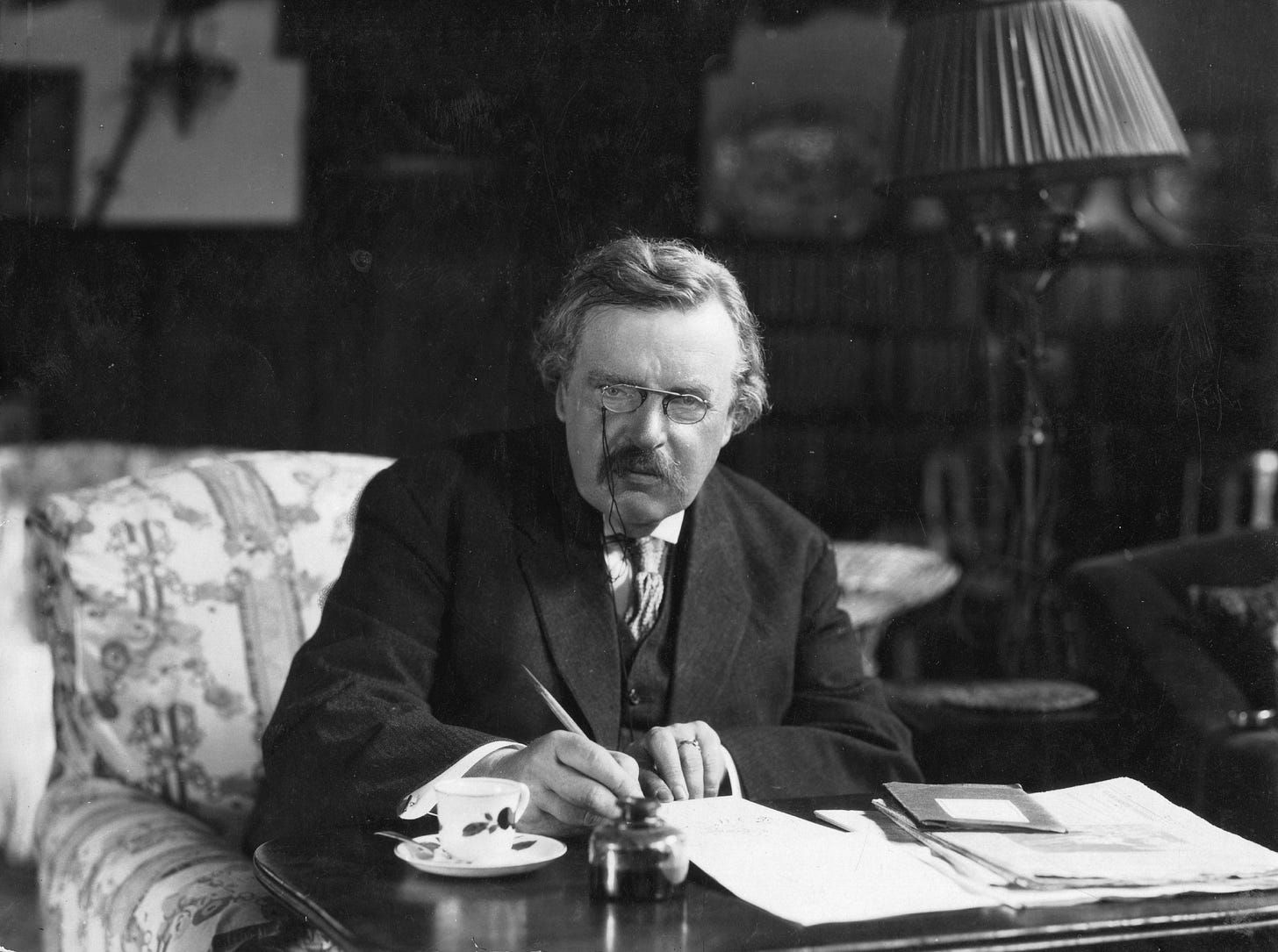

Did G. K. Chesterton predict the Islamisation of Britain?

The great novelist warned of cultural surrender long before it was fashionable.

The creed of multiculturalism has made it difficult to discuss the impact of unfettered immigration. The far right have always opposed it on the basis of racial prejudice and ethno-jingoism. Yet there are authentically liberal concerns to be raised about the problem of political Islam and how all discussions are stifled through accusations of ‘Islamopho…