The inevitability of being offended

An excerpt from my book “Free Speech and Why It Matters”.

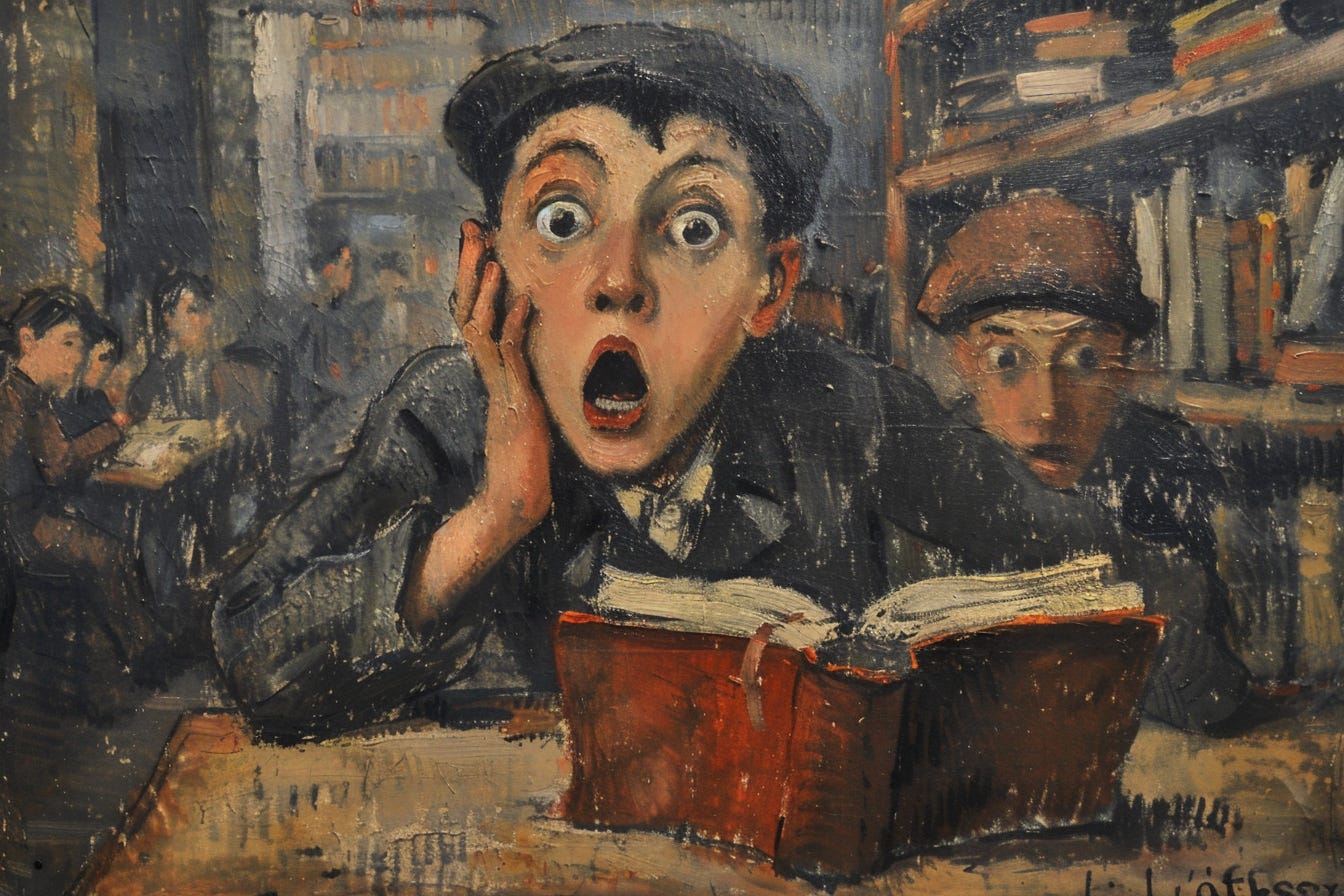

Every human interaction carries the potential to cause offence. There are almost no words that are bereft of connotations, and even silence can be a source of discomfort. We can all therefore agree that to insulate ourselves from the possibility of feeling offended is to withdraw from society altogether.

To a degree, it is healthy to shield ourselves fr…