The Siren Song

Notes from the island of Capri.

Is there anything more joyful than doing nothing at all? Sitting in the piazzetta on the island of Capri, the lazy bustle of tourists in the warmth of spring is tempting me to a second glass of wine. The clocktower watches me from above through its soft blue faience dial, insistently marking each wasted minute. A number of teenagers are loitering on the steps leading up to the Santo Stefano Church, its white dome framed in a spotless sky. The building to its right was a hotel in the 1960 movie It Started in Naples starring Clark Gable and Sophia Loren, and from here I can see the balcony where our hero shared a cheeseburger with a temperamental Italian child.

There is something about Capri that lures even the most active spirit into a state of indolence. The Italians have perfected the art of doing nothing to such a degree that they have a phrase for it – ‘dolce far niente’ – and the most common way for visitors to assimilate is to devolve into lotus-eaters. When the Emperor Augustus came to Capri to recuperate from a stomach illness in AD 14, it is said that he was so dismayed at how lazy his staff became that he dubbed a part of the island the ‘Apragopolis’ (‘City of Do-Nothings’). In 1905, Joseph Conrad spent a few months here hoping that it would stimulate his creative faculties, but even he succumbed to the enervating atmosphere. ‘I’ve done nothing,’ he wrote to Ford Madox Ford. ‘This climate what between tramontana and sirocco has half killed me in a not unpleasant languorous melting way. I am sunk in a vaguely uneasy dream of visions – of innumerable tales that float in an atmosphere of voluptuously aching bones’.

The tramontana and sirocco are the north and south winds that are said to induce this condition among those who stay too long. The aria di Capri smothers the island in a humid haze made heavy with sands carried from Africa. Dante hated it. Some believe it has a disinhibiting effect when it comes to conventional morality. This is the premise of Norman Douglas’s masterful novel South Wind (1917), set on a fictionalised version of Capri which he cannily renames as ‘Nepenthe’: a drug in the fourth book of Homer’s Odyssey which takes away all sorrow and makes one forget. As such, the landscape that Douglas describes has ‘an air of irreality’ which encourages ‘sympathy with sinners’ and sexual vices to be indulged. ‘Northern minds seem to become fluid here,’ says Mr Keith in Chapter 18, ‘impressionable, unstable, unbalanced – what you please. There is something in the brightness of this spot which decomposes their own particles and arranges them into fresh and unexpected patterns’. One may leave Capri with one’s particles intact, but only the bloodless will fail to detect a shift.

The piazzetta is the beating heart of the island, and during the summer it palpitates to an insufferable degree. The pace is slower here in May – still busy, but manageable – so it’s a good time to indulge in reveries of Capri in its former days, before it became a fleshpot for Hollywood stars and fashion icons. Most of the restaurants are decorated with boasting photographs of celebrity clientele: it isn’t uncommon to see snapshots of elderly Italian proprietors nuzzling up to the likes of Sylvester Stallone, Dustin Hoffman and Beyoncé. Not that you are likely to catch sight of any familiar faces during the daytime. From the ferry I had spotted a number of luxury yachts, orbiting the island like so many satellites. Apparently their celebrity owners tend to wait until the evening before disembarking so as to avoid the dreaded hordes of pendolari (daytrippers) and comitive (tour parties).

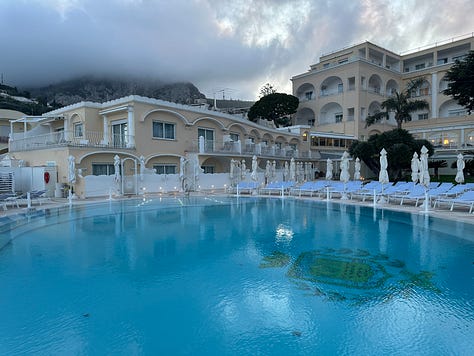

The shopping district of Capri village is a labyrinth of narrow passageways lined with designer boutiques. The Capresi have a long history of extracting money from outsiders, so it feels appropriate that everything is overpriced. I pass by the Grand Hotel Quisisana, built as a sanatorium in the mid nineteenth century (‘qui si sana’ means ‘here one heals’). The hotel has always been a favoured location for the jet set and their various scandals. Elton John was photographed here during the pandemic without a mask, leading to accusations that he was flouting local coronavirus regulations. I have read that when Herman Goring stayed at the hotel he was bitten on the nose by a Welshman’s monkey, a story that I daren’t investigate any further in case it turns out not to be true. Most famously, Oscar Wilde and Alfred Lord Douglas were ejected from the premises in October 1897 following complaints from diners in the restaurant. Homosexuality had been legalised in Italy in 1891 and, in the wake of Wilde’s trial, there had been an exodus of gay men to the continent seeking a more tolerant climate. Unsurprisingly, the diners who objected to Wilde’s presence were English tourists.

— To continue reading this article, please consider becoming a paid subscriber —