Tim Curry: A life of contradictions

In his new memoir ‘Vagabond’, one of the most distinctive actors of his generation reflects on a protean life and career.

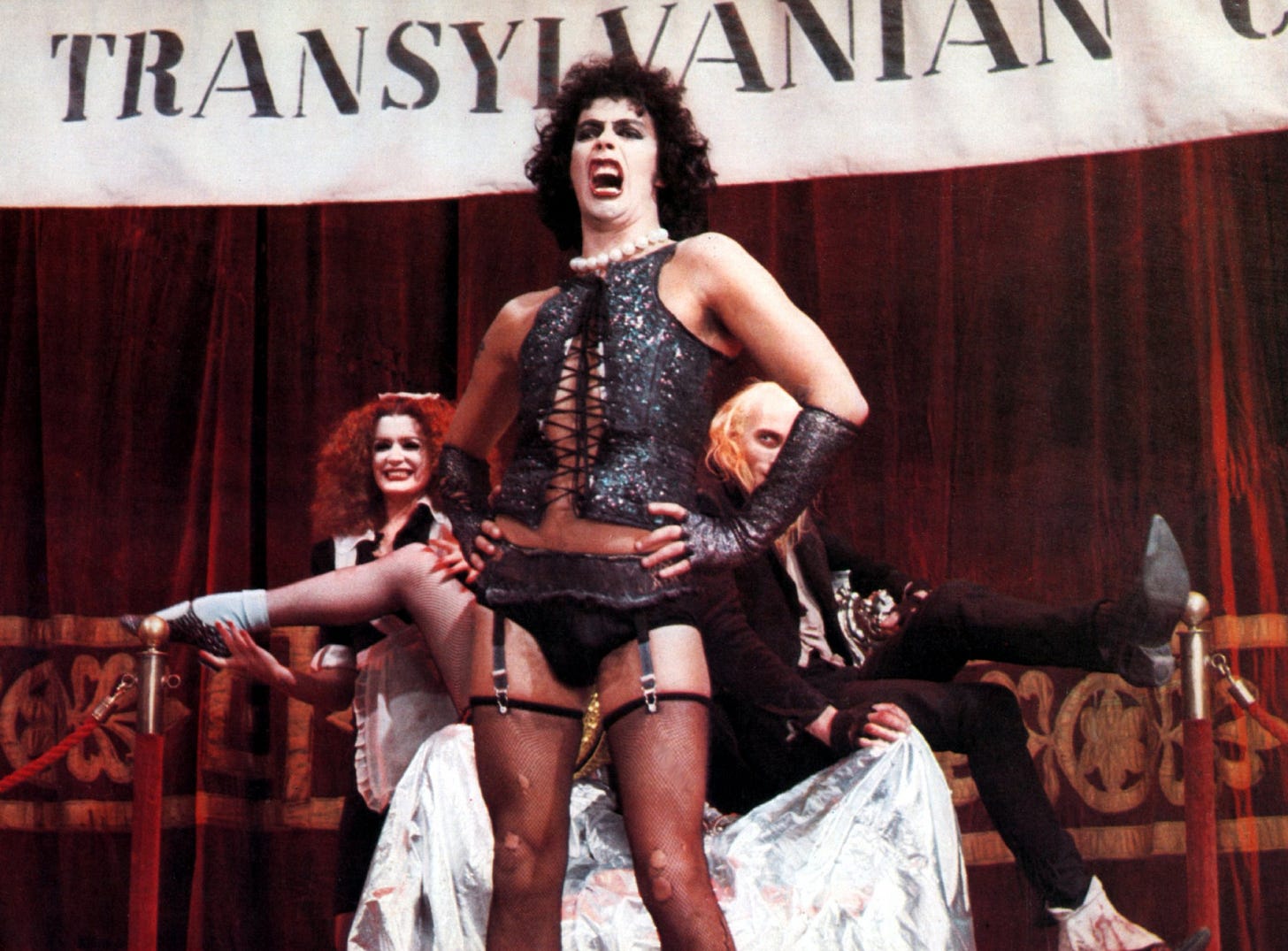

Tim Curry is a shapeshifter. I have a childhood memory of the moment I learned that the demon in Legend (1985), the villain in Annie (1982), the butler in Clue (1985) and the cross-dressing alien scientist in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) were all played by the same man. It…